In a “normal” even-numbered year, the Congress gathers in early January, forms a circle, engages in a team grip and lets out the school cheer, and then disperses back home until State-of-the-Union and budget time a few weeks hence. That time away leads many to conclude that being in Congress is a part-time job at a full-time salary. Well, personally, I would disagree. Most Members whom I have known used that kind of time to seek out their constituents and ask of their concerns, and to update their policy portfolios and ideas. Just like in other walks of life, time for responsible legislators was the most precious resource, and they used it wisely to do their jobs better and improve the lives of the people who hired them.

But what the Members did individually longer ago than I care to admit, and what the institutions do today, are two different things. Politics is played here in Washington, and issues are to be exploited, not resolved. So no big surprise, but the Congress must return to the field and complete a long list of unfinished business. That’s what you get when you procrastinate – you lose your time off and instead must do the work hitherto ignored. So instead of asking you about your concerns or dialing an expert about the issues, the Members are dialing for dollars (well, at least they are talking to you) and hanging around the Washington office waiting for the votes to close out the previous year’s business.

(On the subject of procrastination, did you ever hear about the Philadelphia (my old home town) Procrastinators Club, who back in the nation’s bicentennial year of 1976 decided to address the cracking of the Liberty Bell? The English firm that cast the bell was still in business, and so the club fired off a letter, citing the obvious manufacturing defect and demanding redress. Well, the English firm clearly recognized and respected its responsibility to its customers. Absolutely, they replied, we stand behind our work and our warranty. Just return the bell in its original packaging…)

The Congress has left a lot of unfinished business, but there probably are three items that are most noteworthy to CED. One is the annual appropriations for the ongoing fiscal year (2014). As we discussed earlier, the leaderships of the two parties in the two chambers at least have agreed to an overall appropriations total, but now they and their Members must agree to specific legislation to fund the various agencies within that total. Signs to date are encouraging but not conclusive. More on this effort likely will follow at some future date.

A second bit of unfinished business is the impending collision with the debt limit. The statutory limit has been suspended, but will return to full effect on February 7, with the new limit set at the amount of debt actually incurred as of that date. In other words, immediately upon February 7, the Treasury Secretary must resort to his statutory authorities, aka “extraordinary measures,” aka “tricks,” to raise cash so that the federal government can pay its bills without “borrowing” in the strictest statutory sense of the term. Debt limit crises, a comparatively recent phenomenon, are extraordinarily dangerous. I hope that we will have no further occasion to talk about them over the next two months. But I fear that we will.

The third item near the top of the unfinished fiscal agenda is unemployment compensation extended benefits. Under normal circumstances, unemployment benefits are paid for a maximum of 26 weeks. In periods of high unemployment, when jobs are harder to find, there is an automatic trigger to extend the availability of benefits by 13 or 20 weeks, which varies by the conditions in particular states. However, that trigger is widely considered to be imprecise, and so in the worst of times the Congress is likely to act on its own. Benefits were available for a maximum of 99 weeks (based on the unemployment rate in each state) up until the end of last year, when the extension expired and the duration reverted to prior law. When the December appropriations deal was voted upon, awareness of its omission of action on extended benefits was just arising. Despite a note of protest, the appropriations deal passed, and the Congress went home for the holidays and extended benefits expired. Now, the Senate is debating another temporary extension of benefits, after which (assuming passage) the issue will revert to the House.

What is the right decision? As a recent conversation among CED Trustee members of our Fiscal Health Subcommittee confirmed, this is a many-faceted and hard nut to crack.

A former governor was asked in a private conversation almost 30 years ago on what issue he believed he had spent insufficient time during his tenure. He answered without hesitation: prisons – and added that he believed every other former governor would say the same thing. If you were to ask economists to name an under-researched and under-debated topic, you would not get the same measure of unanimity; but I believe that many, upon reflection, would say unemployment compensation. (Another candidate would be state and local government pensions.) Unemployment insurance (we’ll use UI henceforth) is the first program that economists will mention when trying to explain government’s arsenal of anti-recession programs – what we call “automatic stabilizers.” And yet, although a small group of scholars have done careful work on the intricacies of the program, that research is rarely discussed. UI is a joint federal-state program – and so to a great degree each level of government believes that the other is minding the store, and for that matter intelligent action to improve the program would require time-consuming coordination; and so neither thinks about the program much. UI does not scream for the spotlight, because it does not cost as much as the Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security programs, and it cannot be said to contribute to the long-term budget problem like those others do. And because UI attracts attention only during an economic downturn – when by definition it is too late to correct any structural flaws for that episode – there is a fix-the-roof-when-the-sun-is-shining problem. To borrow an off-the-cuff line from Nobel-winning economist Robert Solow, it is the kind of problem that the policy system tends to try to fix for the crisis after next.

The basic rationale for UI could be expressed in two parts. First, gump happens. People lose their jobs, sometimes through no fault of their own, and it can take time to find new work. In the interim, they and their dependents need to keep body and soul together. UI benefits replace a fraction, on average perhaps one-half, of prior wages (with a low benefit cap that severely constrains benefits for comparatively high-wage workers) to achieve that goal. Second, because looking for work can take some time, perhaps particularly for people with specific skills, UI can buy time to complete a thorough job search. Without UI, a theoretical physicist might have to choose between letting his or her family go hungry and driving a cab. To avoid having a lot of theoretical physicists driving taxicabs instead of working in the lab, we provide UI; and to the extent that this example plays out in the real world, the economy is better off in the long run.

That is one side of the coin. There is another. Some are concerned about the moral hazard associated with UI. The availability of UI benefits can allow people to collect benefits instead of accepting an available job – even if that job is a good one that fits their skills. Employers report interviewing candidates only to hear that the interviewee wants only to have a form checked indicating he or she actively looked for work so as to remain eligible for UI benefits. Or candidates can respond to an offer by saying that they would prefer to report for work several weeks or months down the road when their UI benefits run out. Theoretically, there is little doubt that extending unemployment benefits will increase measured unemployment (although as in the theoretical physicist example, some of that effect might ultimately be beneficial). A leading research paper in this field estimates that every additional week of eligibility for UI benefits increases the average duration of unemployment by about 0.15 weeks (referenced here). And researchers from the Federal Reserve Banks of Cleveland and San Francisco have summarized their work to suggest that the extended benefits now available under federal legislation increase the unemployment rate by up to, but probably less than, one percentage point.

The data do indicate that large numbers of persons who exhaust their unemployment benefits then cease to be unemployed – suggesting that those persons had been postponing accepting a job so that they could continue to collect benefits. However, unfortunately those data do not separate those persons who accepted a job that had previously been offered from those who still could not find work and simply dropped out of the labor force. One study compared the duration of job search among workers who were on unemployment insurance, on the one hand, with the duration among others who were not eligible for UI (including new entrants or re-entrants into the labor force, for example), on the other. That research found that UI beneficiaries had longer periods of job search – but not by much.

There surely are people of limited ambition and responsibility who prefer to go through the motions of a job search while to the maximum possible degree enjoying leisure and collecting UI benefits. But there certainly are others who are enduring heartbreak in a desperate search for work, and whose families are hurting financially. Do we govern for the exception, or do we govern for the rule? And which is which?

(I appeared on a radio call-in show during the last days of congressional debate over the Tax Reform Act of 1986, when the major outlines of the final legislation were fairly clear. One caller was a woman who said that she had routinely high medical bills, and who was upset that the new law would allow the deduction of medical expenses only in excess of 7.5 percent of income, whereas the prior law had allowed the deduction of expenses over 5 percent of income. She was unhappy because she would receive less tax relief for her medical bills. Meanwhile, the law increased the personal exemption that all taxpayers received, and the standard deduction received by taxpayers who did not itemize. All of those provisions, taken together, provided a net tax cut for most taxpayers; and the increase in the standard deduction, to the extent that it allowed taxpayers to pay less tax without itemizing their deductions, provided a significant simplification to those taxpayers. Was that combination of changes in the law an example of a meritorious achievement of the greatest good for the greatest number? Or was it an unfair imposition on the few taxpayers who faced an unusual but painful circumstance? This is an example of the kind of calculation that public policy must make in almost countless instances – including in decision-making on unemployment compensation.)

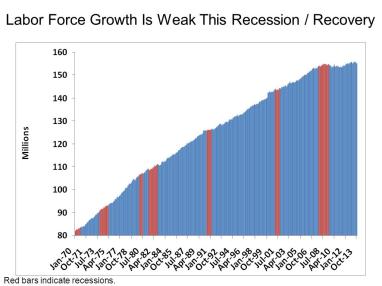

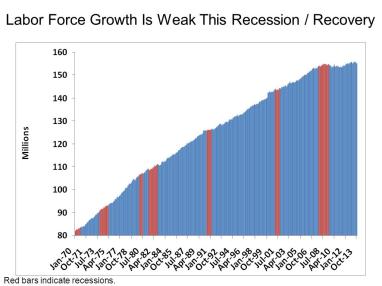

Today’s economic circumstance is unprecedented in our lifetimes; we have endured the deepest recession since the Great Depression, whose collateral damage has hindered the subsequent recovery. The job market became so weak in some localities that large numbers of people found job search fruitless, and ultimately dropped out of the labor force (see the following chart). (One indictment of UI is that it has encouraged people to refuse job offers, and so has made unemployment and the labor market look worse than they really or potentially are. Technically, however, to collect UI, people must engage in job search, and therefore would not be counted as having dropped out of the labor force.)

This downturn has been felt disproportionately in several geographic regions of the country, fairly clearly identified by collapses in housing values. Imagine a family whose breadwinner has lost his or her job in a locality where the worst of the housing bubble has crushed business conditions broadly. There is no work in the unemployed person’s field, not much in other fields, and for that matter, there are experienced and unemployed persons in just about every field, so job training (such as it is, which is one of the greatest shortfalls of government) and a change of career are not the answer. So the family might want to relocate to find a job – but the family’s home mortgage is underwater, and so they cannot move.

The federal government has taken action by extending unemployment benefits fairly broadly (with some targeting by the state unemployment rate – which has become an imperfect indicator of the condition of a state’s economy, because the widespread exits from the labor force distort the measured unemployment rate). In the worst labor markets, and for families in the extreme Murphy’s Law, Catch-22 kind of circumstance just described, that would make sense. Those people could hunker down and keep looking for work until the housing market and the local economy improve. But to the extent that federal action continues very long durations of benefit eligibility – as of last year, almost two years – in local labor markets that are stronger, people who look seriously for work would have a good chance to find it, and so the greatest practical effect would be to tempt others to refuse job offers and collect benefits for long periods of time.

So what is the right policy response? We might leave the decision up to the states. Let each state decide whether its labor market is weak enough to justify continuing extended benefits. That would work in one dimension, but the states with the weakest labor markets are by definition those with the least ability to pay to extend benefits. One reason for an at least partially national unemployment system is that it allows the sectors of our diverse economy that are strong in any particular economic cycle to help to foot the bill for the recovery of those sectors that are weak – knowing that the tables might be turned in the next recession.

So perhaps we could have federal action, but delineate it more sharply based on the condition of each state, with more help for those whose labor markets are weak, and less help for those that are strong. But such an approach raises its own challenges. Beyond the fact that our labor market indicators are deranged by this unprecedented downturn, the Congress always has had difficulty with the distribution of aid among the states. It might be the right thing for a legislator to step forward and volunteer that his or her state or district does not need help. But that would not be a good way to begin the campaign for the next election. Every state or district has some people who are unemployed and cannot find work. As an elected representative, to suggest that your constituency is not in need is to belittle those voters, and their friends, and their communities. That is part of the reason why the Congress never has had much success at the kind of geographically compensatory programs that you would think would be a key responsibility of the federal government of a large and diverse nation, and why such “formula fights” usually boil down to a relative uniform distribution of support regardless of the real diversity of need.

In sum, this is a complex issue with weight on both sides of the scale, in terms of both the nature of the problem and the likely success of the alternative remedies. Where people come down will depend upon their policy judgment, and also their local circumstances and personal values. We might want to think now about longer-term structural improvements – but the long-term forecast is that once it stops raining, the sun will shine again, at least for a while. Maybe for the crisis after next.

mischief. There are inevitably small details that are tucked away out of immediate view. Some of those have come to light already, but others might show up only after the bill has become law. The fraternity of people who can read appropriations language is fairly small, and they are in overload this week. So be prepared for news flashes several days or even weeks down the road.

mischief. There are inevitably small details that are tucked away out of immediate view. Some of those have come to light already, but others might show up only after the bill has become law. The fraternity of people who can read appropriations language is fairly small, and they are in overload this week. So be prepared for news flashes several days or even weeks down the road.